[ad_1]

A collaboration between three artists—Millie Brown, Camille Obering and Benyaro (aka Ben Musser)—Photosymphony: A Live Plant Orchestra began as a real-life installation at Guesthouse, a private art space in Jackson Hole (also owned by Obering and Musser). It has since evolved into a lush, sensual three-minute film. Through Priscilla Fraser—director of LA’s MAK Center for Art and Architecture—Obering met Brown and explained the philosophy and mission behind Guesthouse: to invite creatives of all kinds to visit and show their work to a different audience in picturesque surroundings. Working off the idea, Brown mentioned a technology that captures plant frequencies and they decided to work together on an artwork that employed that tech. With communication and connectivity between nature and humans as the overarching theme, Photosymphony was conceived.

We spoke with Obering and Benyaro about collaborating on such a special project, the clever technology that captures plant frequencies, our relationship with nature, and how thoughtful flowers really are.

Photosymphony: A Live Plant Orchestra from Camille Obering Fine Art on Vimeo.

How did the collaboration play out between you all—in terms of development and then execution?

Camille Obering: Millie and I conceptualized an installation that would fill a space with native plants to the region. We worked to identify native plants and curate them in a way that reflected the environment we were seeing in this region. As we honed the idea of wanting to communicate to the audience the idea that the universe and all its life is interconnected we settled on using sounds of the sun, various planets, the womb, female orgasm, among others, all backed by instruments: violin, viola and cello. Millie researched and found the abstract sounds for Benyaro to sample. Neither Millie, nor I knew how to bring the vision to life sonically as the technology is very complex. Benyaro came onto the team to execute that part of the piece and was instrumental in pulling it off.

Benyaro: There was an entire visual aesthetic that needed to be curated and tended to as well as a substantial audio production/sound design, on top. Millie and Camille needed a sound designer to produce the audio portion of the installation and we all began to feel like I could step into that role and create the soundscape, though I had never worked with this technology before.

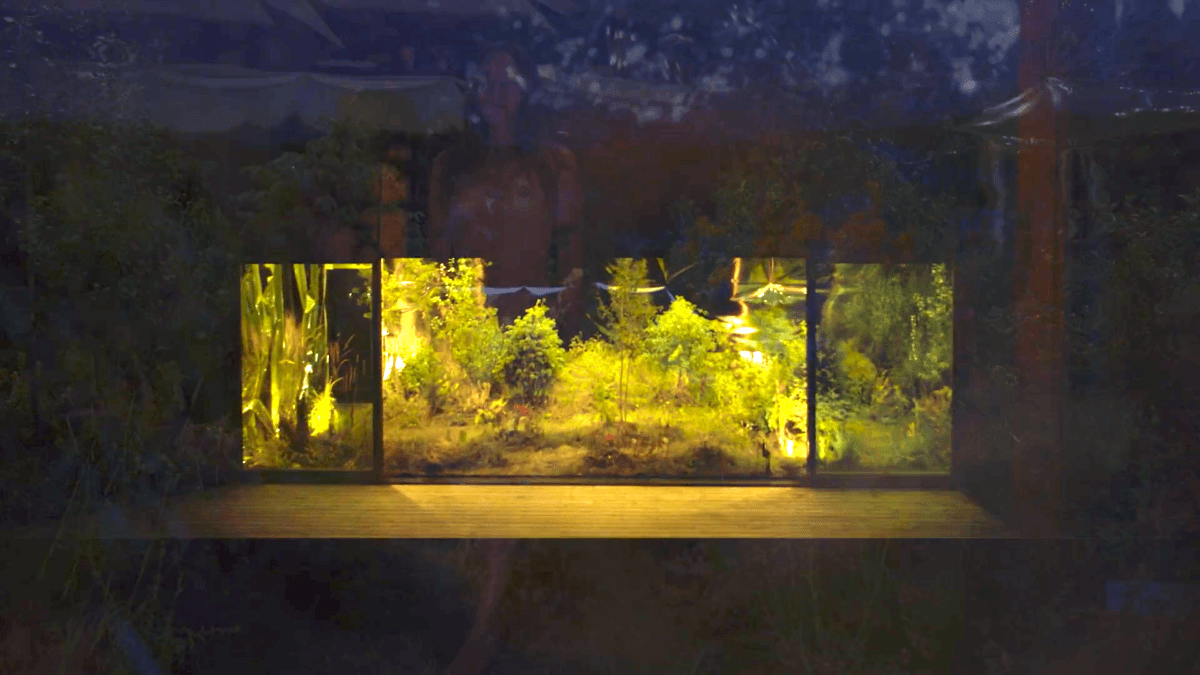

After many hours of research, trial and error, and interfacing with plants, I began to understand the infinite possibilities and ways in which we could approach the sound design in order to create something beautiful and unique. I then worked closely with Millie to achieve the soundscape we wanted. Visually, I had the idea of putting mylar [aka BoPET, a type of polyester film] all over the gallery walls to reflect the mountains and natural outdoor beauty plus help get the plants more light so they could survive a bit longer. The mylar ended up giving the piece a very interesting visual element.

The film is about connectivity between plants and people—how important do you feel that connection is? Do you think it’s a relationship humans need to work on?

CO: As we became an industrialized world and luxuriated in many of the conveniences that has brought humans, we lost sight of the importance of nature and took it for granted. However in recent years, as we see our natural resources being depleted, we are becoming more aware of the importance of these resources for our survival, comfort, and joy. The challenge we face now is how to maintain the quality of life we have grown accustomed to while living in a balanced ecosystem.

More than one of the plants I worked with would try to find notes in the key of the classical piece we were listening to

B: On a large scale I agree. On a smaller scale, the idea that plants and humans are feeding off each other’s vibrations is a connection I just discovered through this project. This project enlightened me and made me aware of just how in-tune plants can be with each other and with the vibrations we give off as humans. Part of my experimenting with the plants was to see how they reacted to different music, in different keys, and I can honestly say that more than one of the plants I worked with would try to find notes in the key of the classical piece we were listening to. I think we should give plants more respect and realize they are doing way more than we give them credit for. Sorry vegetarians.

This project combines science, visual art, music, tech and nature—why was it important for you to have them all work in orchestra?

CO: More and more we live in a world where there is cross-pollination between different disciplines. They are no longer siloed because there is a growing understanding that each discipline has the potential to feed into another and more knowledge from diverse perspectives can be revealed. This artwork was able to bring all of those ideas succinctly under one installation, which was quite an accomplishment and perhaps why it resonated with people. It was akin to being inside of a living, life-sized diorama where we were able to witness the scientific process of photosynthesis audibly (and visually) in real time.

B: To fulfill the potential of this installation, we needed to be successful on many fronts. Visually, it needed to look beautiful and attractive so people would want to look, walk through, and stop to enjoy. Sonically, the project had infinite possibilities. We could’ve had the plants all firing human sounds, words, or we could’ve had plants play the piano, or brass, or woodwinds, or the sounds of car engines. Whatever we could sample, we could make a plant say or “fire.” Because we decided to let the plants fire notes as randomly as they wished, our task was to hone the soundscape so it was not overbearing or anxiety-producing—which was challenging considering an Aspen tree firing violin can quickly sound like an Alfred Hitchcock score. In order for all of the audio to work, the extensive tech needed to be understood, correctly interfaced and dialed. As the installation aged and the plants lacked water and light they would otherwise be accustomed to, the soundscape became less active, as natural scientific processes like photosynthesis slowed. Without combining all of these elements successfully, the installation could have come up short.

Tell us some of the lessons and surprises that occurred while working on the project.

CO: As Benyaro mentioned, hearing plants react to different music, in different keys, and try to find notes in the key of a piece of music we were listening to and strive to stay there was amazing and made me a believer.

B: Big ideas can be executed with a dedicated, hard-working team. Also, plants give off a lot of water vapor, and smell amazing.

Can you tell us a little about the sound design and tech used to capture and translate the plant frequencies?

B: MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface) was created in the early 1980s as a way to connect musical instruments with computers in order to play, edit and record music. In recent years, a small company called MIDI Sprout (now PlantWave) created a small system that captures the biorhythms and tiny electrical currents a plant gives off when photosynthesizing or carrying out intracellular processes; the MIDI Sprout technology then turns the frequencies and information from the plant into numerical values and thus into the language of MIDI. The MIDI information gets sent to a synthesizer, in this case on my computer, and from there we determine what sample (violin, human noise, etc) a plant will fire when it gives off a particular frequency or information.

We program that each time a plant fires X, sample Y will sound. For the plants connected to violin, viola, and cello, we gave the plants the full range of the instruments and if the plant fires a C#4, a C#4 would be played for the duration the plant gives off the info. Sometimes the notes were short, sometimes they were longer. Completely random and up to the plant. For the more abstract noises, a different plant could fire a C#4 (etc) and it would play whatever sample we associated with that note, perhaps the sound of the sun, or a baby cooing. It took hours to curate the samples in a way that made the soundscape balanced and cohesive. And sometimes plants were talkative, sometimes they were not, which made testing and actual performance unpredictable, but very interesting. After the information from the plant was synthesized in the computer, the signal is sent back out to the plant’s individual speaker and the sound is played via the speaker. All of this happens nearly instantaneously.

Having a little distance from the piece now, do you view it differently? Does it evoke different feelings than it used to?

CO + B: It was such an intense undertaking to design, create, install and deinstall Photosymphony that yes, it’s taken some time and space to realize just what an amazing, unique thing we ultimately created. We run into folks who experienced it and everyone talks about how much they loved it and want to know how it went and if it will happen again somewhere, which shows what an impact it had on people. We have grown more proud of our achievement as time passes.

What mood or emotion do you hope it stirs in viewers?

CO + B: Joy, wonder and curiosity.

Images and screenshots courtesy of Camille Obering and Benyaro

[ad_2]

Source link https://coolhunting.com/culture/photosymphony-live-plant-orchestra/